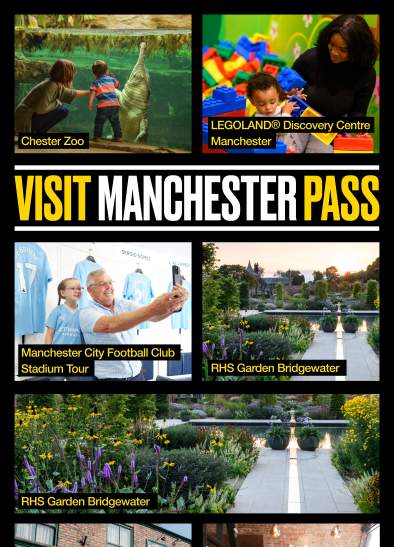

By Melanie Tebbutt, Professor in History at Manchester Metropolitan University and part of the Manchester Centre for Public History and Heritage and Head of Youth History in the Manchester Centre for Youth Studies

Boxing at Collyhurst and Moston Lads’ Club, which celebrates over a hundred years of boxing tradition this month, is a reminder of the contribution that Lads’ Clubs and their successors have made to Manchester’s amateur boxing heritage and local communities.

Lads’ clubs originated in the late-Victorian period, when they were established by philanthropists in many working-class areas of Manchester and Salford as an alternative to hanging around the streets or being drawn into the ‘scuttling gangs’ which were so common in poor districts. Thriving girls’ clubs were also set up, although they were fewer and tended to receive public less attention until the interwar years.

Less formal than the Boys’ Brigade and Scouts, Lads’ clubs were more successful than both organisations in drawing in poorer and older working-class boys. They often attracted hundreds of members, although their influence is largely forgotten now, other than in the case of famous survivors such as Salford Lads’ Club, on Coronation Street, Ordsall,[1] now open to boys and girls and which is cemented into pop culture memory by the iconic photo of the Smiths, taken in 1986. The Club entrance in the background of this famous image gives a glimpse of the substantial buildings in which lads’ clubs were often located and which became a focal point for the communities in which they stood. Strongly embedded in working-class districts, such clubs had a transformative effect on many young people and their communities, fostering life-long relationships and loyalties across generations. Larger clubs were often well-equipped with purpose-built club rooms and gymnasia, offering a mix of recreational, educational and sports activities which included football, gymnastics, cricket, holidays in the countryside, and boxing. These buildings, infused with the complex local meanings of place and belonging, were integral to the lived landscapes of many working-class districts, although their affective and architectural heritage has often been ignored, in contrast to the attention devoted to ‘important’ civic buildings, old warehouses and gentrified Victorian terraces.

The heyday of lads’ clubs was before the Second World War and many were in a sorry state by the 1960s in the face of redevelopment and more varied entertainment alternatives for the young. Their buildings, in a state of disrepair, were expensive to maintain, rarely conserved and often pulled down, although not without opposition. In 2011, local people tried unsuccessfully to stop the demolition of Ardwick Youth Centre, formerly Ardwick Lads’ Club, a much-loved meeting place for generations of youth. Founded in 1897, Ardwick Lads’ Club moved in 1898 to ‘handsome’ purpose-built premises, which included a large gymnasium with a gallery on two sides for spectators, dressing rooms and washing facilities, reading room, billiard room, and two skittle alleys. Ardwick was Manchester’s largest lads’ club in the interwar years, with 2,000 members. It was also home to a boxing club which flourished during the ‘golden’ decades of boxing in the 1930s and 1940s. Possibly the oldest purpose-built youth club still in use in Britain by the time of its closure, Ardwick’s boxing club was the last group remaining when the club’s physical history finished, after a ‘last ditch attempt’ to save the building on historical and architectural grounds was turned down. Ardwick Youth Centre was demolished in 2013 but the tenacity of the boxing tradition there continued when its boxers finally found a new permanent home in the John Gilmore Centre in Openshaw, opened in March 2019, as part of the Beswick community hub regeneration project.

Histories such as these illustrate the key role that boxing clubs often played in lads’ clubs and their capacity to survive even after a broader range of club activities had disappeared. Each boxing club had its own character, a mix of discipline, self-denial and hard work which when managed effectively, could bring out the best in individuals and contest the hyper-masculinity, disparagement of female participation and homophobic attitudes which marred some clubs. The distinctive atmosphere, values and grassroots success of clubs like Ardwick, and Collyhurst and Moston, owed much to the personalities of individual club leaders.

Local boxing heroes

The figure who stands out in the postwar history of Collyhurst and Moston Lads’ Club is Brian Hughes (far left in image), the highly respected amateur boxer and trainer who influenced the club for the best part of 50 years and whose boxing mantra was making tough lads into ‘human beings, not bullies’. Born in 1940 and brought up in Collyhurst, Hughes ‘knew how tough it was’ to grow up in a place where ‘The only way you got respect really was if you could fight’. He was familiar with Collyhurst Lads’ Club as a boy and became involved in boxing in his teens, visiting local gyms and training every evening and weekend at the Lily Lane Youth Club in Moston. As a poor lad with few prospects, the discipline and focus he experienced there had an immense impact on his self-belief: ‘All’s I know is from leaving school, I stopped running with a gang and I got into sport, I got into boxing, and really truthfully, it changed me whole life’.

Collyhurst Lads’ Club had closed by the 1960s but Hughes remained true to his belief in the potential of local youth and was persuaded to reopen it after criticizing the lack of facilities for them, setting up a successful football team and a boxing club, both of which won many cups and leagues. Collyhurst Lads’ Club was demolished in the clearance programmes of the 1970s and in 1976, Hughes and his boxers moved into their current premises on Oscar Street, north Manchester, as Collyhurst and Moston Lads’ Club, where he became Chief Coach. Brian Hughes’s work in the community was recognised with the award of an MBE in 2000. He retired from the club in 2011, having spent a lifetime pulling together resources to help sustain it. In 2018, the respect in which he continued to be held was evident after 6,000 people signed a petition in favour of the City Council naming a road in Collyhurst - Brian Hughes Close - after him.

.jpg)

Tommy McDonagh, a former amateur and professional boxer who now runs Collyhurst and Moston Lads’ Club has been boxing there since he was eight-years-old and is well aware of the personal and club debt owed to Brian Hughes. When the club took part in an engagement project called Passions of Youth in 2014-15 (picture below shows the project working with the archives), which was supported by Manchester Metropolitan University (ManMet) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), the teenage boxers who were involved naturally explored Hughes long- standing involvement with the club, which they recorded in a film called ‘100 Years and Still Fighting’. While they weren’t much interested in history at school, they were enthused about the history and heritage of their own local boxing traditions and the project used their passion as hook through which to encourage them to develop research skills and learn about film-making. Through visits to Manchester Metropolitan University, the People’s History Museum, Archives+ at Manchester’s Central Library, the North West Film Archive at ManMet, and the Working-Class Movement Library in Salford, they discovered more about the history of boxing and their district and learned how to tell these stories through film-making.

The teenagers who participated were well aware of ‘the bad press’ often directed at Collyhurst, which in the words of one young boxer is not far away from the ‘posh bits of Manchester, but it sometimes feels a world away’. They were very proud of Collyhurst and Moston and the contribution they were making through the project to its boxing history.

As another boxer put it, ‘It’s good thinking we’re part of a tradition, that lads have been coming here doing what we do for a hundred years’. Their film was not only an opportunity to express their feelings about Collyhurst and Moston Lads’ Club but also to remember those who have contributed significantly to Manchester’s boxing scene, older ‘local heroes’ such as Brian Hughes, described as ‘an institution in UK fight circles’ and one of boxers’ best trainers. Importantly, they captured something of how the atmosphere and tradition Hughes established at Collyhurst and Moston went beyond fighting. Making champions was always important but as he observed in 1980s archive footage in the North West Film Archive which was used in ‘100 Years and Still Fighting’:

It’s not just going into the gymnasium and teaching ‘em how to throw a left jab or a right cross or defensive work, it’s much more, it’s deeper than that. The effect that the Collyhurst club … has on the kids that come here is that firstly you teach them as human beings… There’s no jobs for them, so you’re going to have to do something. These kids need to be shown the way, there’s more to life than bingo and to crime and the mugging people. And these kids’ll do it.

Hughes (pictured below) had a reputation for looking ‘after the kids like a father figure’ and helped establish Collyhurst and Moston Lads’ Club as a community hub which has inspired huge affection across the generations. As one of the boxer filmmakers put it: ‘Boxing’s just a tradition with me family. Me dad did it, me uncle did it and now I’m starting to do it and I’m going to carry it on’. Others expressed pride in how, ‘Lads have been coming here forever’, and ‘have produced some of the best talent in British boxing’. Former members often became trainers themselves or introduced their children to the club’s family-like atmosphere, which now includes girls and young women.

‘I love this place. It’s my second home’. ‘You do learn discipline, hard work keeping out of trouble and hope. Being who you can be, being proud of where you’re from and who your mates are. It’s like a family, Collyhurst and Moston’. (A Collyhurst and Moston boxer)

.jpg)

As Hughes himself put it: ‘at the end of the day, your real beliefs have gotta be that you’re doing and trying to set him a better example. You’ve gotta make him go out into the world feeling that he hasn’t been let down by a human being and that you’ve shown faith in him, and if he goes out in some other field, his faith and his dedication, his application, will pay off for him’.

The teenage film-makers involved with ‘100 Years and Still Fighting’ were familiar with Brian Hughes’s reputation through their club’s history. They were, however, unaware until the Passions project of another significant Mancunian boxing hero from a different part of Manchester, Len Johnson, born in Clayton in 1902. Johnson’s mother was Irish and his father was from Sierra Leone and the Collyhurst and Moston boxers, proud of their own boxing prowess, were shocked to find that Johnson, despite being the country’s best middle-weight and one of the world’s best boxers of the 1920s and 1930s, was never allowed to fight for an official title in Britain because he was black. Johnson fell foul of the colour bar, not lifted until 1947, which was responsible for boxing’s ‘infamous Rule 24’ that title contestants must have two white parents. Forced off the professional boxing stage by racism, Johnson eventually retired from the official boxing arena in 1933, to earn his living running a travelling boxing booth, a common feature of fairgrounds in the interwar years, and which was where he had originally learned to box through his father’s own travelling booth.

Increasingly politicised, Johnson joined the Communist Party (CP) and was the Manchester CP delegate to the Fifth Pan-African Congress, the most important Pan-African Congress of the colonial period, which took place from the 15th-21st October 1945 at Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall, All Saints. This landmark event in the history of African liberation is commemorated by a red plaque to mark its significance in the struggle to end colonial rule.

Johnson developed a strong friendship with the African-American singer, actor, and activist for civil rights, Paul Robeson, and became a prominent community leader and activist in Moss Side after the Second World War. Mike Luft, interviewed for ‘100 Years and Still Fighting’, knew Johnson through his own father, who had fought for him. In Luft’s view, Johnson’s campaigning on behalf of his fellow boxers to ensure ‘they didn’t get battered like he suffered’, and his battling against discrimination and for civil rights make him an important example of ‘how there are different ways to fight, both in the ring and outside it’.

‘Maybe that’s the thing that young boxers should think of. What am I going to do when I finish boxing’. I mean, Len was really strong on that, and we should have young boxers who move on to the next stage of a career and maybe the discipline which they’ve learned as a boxer will help them develop that next stage’.

The young boxers who made t he film (pictured), reflecting on the skills that boxing had given them, put it in their own way:

he film (pictured), reflecting on the skills that boxing had given them, put it in their own way:

‘Me mum doesn’t like me doing boxing, but I love it, it makes me who I am. When I do boxing, I feel like I’m doing something positive with me life’.

‘Not all of us will be professional fighters, Olympic boxers or like Len Johnson but I think the stuff we learn here in this gym will stay with us all our lives’.

‘100 Years and Still Fighting’ demonstrates the living, evolving working-class heritage of amateur boxing in Collyhurst and Moston and the role that positive change-makers can have in fostering among the young a sense of community responsibility and belief in possibilities beyond boxing. Lads’ clubs may be largely forgotten but the film, when shown in celebratory events at the end of the Passions project, at the Miners’ Community Arts and Music Centre and FC United Community Football Club, received an enthusiastic reception, testament to the community spirit and pride sustained in working-class districts long after club buildings have fallen into disrepair or been demolished.

Photography:

Image 1: 100 Years and Still Fighting - Collyhurst and Moston Lads Club. By Passions of Youth

Image 2 - Brian and Damian Hughes, Collyhurst. Photograph courtesy of Damian Hughes and family.

Image 3 - Brian Hughes and his family at the official opening of Brian Hughes Close, Collyhurst, in 2018. Photograph courtesy of Damian Hughes and family.

Image 4 - Jim Dalziel, copyright Passions of Youth.

Image 5 - 'Brian in the corner'. Photograph courtesy of Damian Hughes and family.

Image 6 - Len Johnson, with thanks to Shirin Hirsch.

Image 7 - Jim Dalziel, copyright Passions of Youth.

[1] Dates from 1903.