The nineteenth instalment as part of an ongoing series for Haunt Manchester by Dr Peter N. Lindfield FSA, exploring Greater Manchester’s Gothic architecture and hidden heritage. Peter’s previous Haunt Manchester articles include features on Ordsall Hall, Albert’s Schloss and Albert Hall, the Mancunian Gothic Sunday School of St Matthew’s, Arlington House in Salford, Minshull Street City Police and Session Courts and their furniture, Manchester’s Modern Gothic in St Peter’s Square, what was St John’s Church, Manchester Cathedral, The Great Hall at The University of Manchester, St Chad’s in Rochdale and more. From the city’s striking Gothic features to the more unusual aspects of buildings usually taken for granted and history hidden in plain sight, a variety of locations will be explored and visited over the course of 2020.

In this article he reflects on Chetham’s Library, Manchester. The Library is currently closed to visitors due to Covid-19 measures, but it has an informative website you can visit here, including fascinating images from ‘The Manchester Scrapbook’, a wide-ranging blog and a selection of learning resources from home.

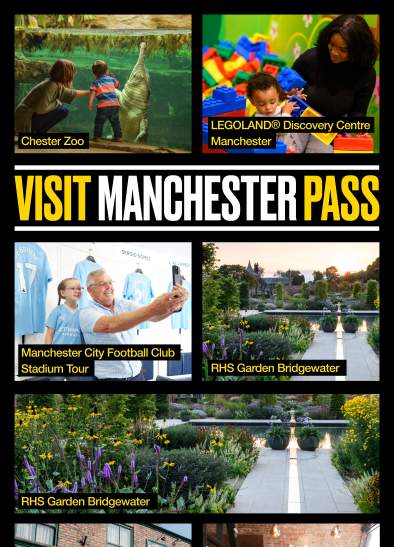

Pictured below - The Presses at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

.jpeg)

Dr Peter N. Lindfield FSA is a Senior Research Associate in the Departments of English and History at Manchester Metropolitan University. He has published widely on Georgian Gothic architecture and design broadly conceived, as well as heraldry and the relevance of heraldic arts to post-medieval English intellectual, cultural, and aesthetic culture. Last year, as part of Gothic Manchester Festival 2019, he co-organised an event at Chetham’s Library Baronial Hall with Professor Dale Townshend titled ‘Faking Gothic Furniture’ (it also features, along with The John Rylands Library, in a previous article by Peter, here). This involved discussing the mysterious George Shaw (1810-76), a local Upper Mill lad who developed an early interest in medieval architecture and heraldry, going on to create forgeries of Tudor and Elizabethan furniture for a number of high-profile individuals and places at the time, including Chetham’s!

Currently Peter is completing his Leverhulme-funded research project exploring forged antiquarian materials in Georgian Britain, and also working on the recently re-discovered Henry VII and Elizabeth of York marriage bed, which itself was the inspiration behind many of Shaw’s so-called ‘Gothic forgeries’.

The Zenith of Manchester’s Gothic: Chetham’s Library

The Cathedral is surely what most people would consider to be Manchester’s oldest surviving Gothic building dating to the medieval period (Fig.1). However, large parts of the Cathedral were built or rebuilt after its initial foundation in 1421; in particular it was significantly modified in the Victorian period. Chetham’s, on the other hand, escaped such widespread and significant interventions by the Victorians (Fig.2). It can and should be considered the finest surviving example of medieval architecture in the city.

Below - Fig 1: Interior of Manchester Cathedral. © Peter N. Lindfield.jpeg)

What is now known as Chetham’s Library was built in 1421 in connection with what is now the Cathedral, but, in the fifteenth century, was a collegiate church. As such, Chetham’s, see here, is a modest stone’s throw from the Cathedral. Grade I listed by Historic England (listed on 25 February 1952, List Entry Number: 1283015, here), Chetham’s is one of the most truly spectacular, historically important, and irreplaceable examples of built heritage not only in Manchester, but in Britain at large. Indeed, its national significance was recognised by Historic England in its 2018 initiative, ‘Irreplaceable: A History of England in 100 Places’, here and here.

Chetham’s Library is a truly historic gem: it was established, like Manchester’s Collegiate Church, by Thomas de la Warr[e], fifth Baron de la Warr[e] (d.1427). After the Dissolution, in particular the Chantries Act of 1547, it was converted for use as a town house by Earl of Derby; the property was sequestrated during Commonwealth, and finally purchased in 1654 by Humphrey Chetham’s executors for the intended repurposing as a hospital—a charity school—and library. It is from this last transfer of ownership that the property took its name; Chetham’s became England’s earliest freely accessible public library, and it is designated by Arts Council England as a site of national and international importance.

.jpeg) Above - Fig.2: Exterior of Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Above - Fig.2: Exterior of Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

If you haven’t had the pleasure of undertaking research at any of the UK’s ancient and peerless research libraries, such as the College Libraries at Oxbridge, none more spectacular than the Duke Humfrey’s Library within the Bodleian (Fig.3), then Chetham’s offers you the best glimpse into the world of ancient learning and scholarship. It is, indeed, a refined ‘ivory tower’. But, unlike other precious libraries, Chetham’s was opened as a freely accessible library for all. Such a survival of medieval architecture is especially very rare in Manchester, and together with the library’s now fantastic collection of rare or unique historic manuscript material makes it peerless.

Below - Fig.3: Interior of the Duke Humfrey’s Library, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Diliff (CC BY-SA 3.0).

.jpg)

The Library complex is built around a cloister (Fig.4), includes rooms such as what are known as the Baronial Hall and the Reading Room. The library’s presses are contained on the first-floor range, with the presses’ books now protected behind gates installed in the eighteenth century. The Baronial Hall (Fig.5) is a survival of such great halls found in medieval timber-framed buildings, such as Ordsall Hall, see here, and a notable survival is the oak screen that is a traditional feature of such rooms; designed to keep the draught out and shield comings and goings along the corridor behind. Similar examples can be seen at numerous country house halls, such as at Ordsall Hall, Salford, and Audley End, Essex.

Below - Fig.4: Chetham’s Library Cloisters. Vicente (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Fig.5: The Baronial Hall, Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Upstairs, the distinctive and glorious smell of old books and manuscripts pervades. The bookcases, or, more properly, presses, are dark stained, indicating age (Fig.6), and this leads through to the reading room (Fig.7). At the centre of the room are 24 Cromwell-type chairs surrounding a large table; these all date from the 1650s when the complex was re-purposed as a library. The most striking part of the room is the decoration on the wall above the chimneypiece: a portrait of Henry Chetham sits directly above the chimney mantle, and in the tympanum above the panelling is Chetham’s coat of arms (Fig.8). Notably the arms are flanked by obelisks wrapped in olive leaves, representing peace eternal, resting on a foundation of books; even the coat of arms is sat upon the carved reproduction of three stacked books. This is a fitting memorial to the library’s founder. This room is also notable as containing the Gothic alcove where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels worked in the summer of 1845 (Fig.9).

Fig.6: The Presses at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Below - Fig.7: The Reading Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Below - Fig.8: Detail of the tympanum carved decoration in the Reading Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Below - Fig.8: Detail of the tympanum carved decoration in the Reading Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Below - Fig.9: The ‘Marx Engels Alcove’ at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Another fascinating room within the library complex is what is now known as the Audit Room (Fig.10). Originally used by the Warden of the medieval college, this space has layers of precious heritage. Mirroring certain aspects of the Cathedral’s vaulting, the Audit Room’s ceiling is made from timber and separated into nine sections. Above the wooden panelling running around the walls of the room is a fine example of seventeenth-century floral plasterwork (Fig.11)—note how there are no Gothic architectural elements in this plasterwork, but the pattern reflects seventeenth-century fashion.

Below - Fig.10: The Audit Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Below - Fig.11: Detail of the plasterwork in the Audit Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Below - Fig.11: Detail of the plasterwork in the Audit Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Perhaps as striking are a suite of eighteenth-century ladder-back mahogany chairs made in a hybrid of Gothic and Rococo forms popular in especially the 1750s and promoted by fashionable London-based designers, including Thomas Chippendale (Fig.12). The Rococo is characterised by organic C- and S-shaped scroll work, asymmetry, and flowing lines (quite unlike Classicism), and exemplified by this design by Chippendale now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Fig.13). The notable Gothic features of the Chetham’s Rococo-Gothic chair are the quatrefoil piercings in the back rails, visible in Fig.14.

Below - Fig.12: Thomas Chippendale, Commode. 1761. Rogers Fund, 1920, 20.40.1(47). © www.metmuseum.org

Below - Fig.13: Thomas Chippendale, Gothic Chairs. 1753. Rogers Fund, 1920, 20.40.1(22). © www.metmuseum.org

Below - Fig.13: Thomas Chippendale, Gothic Chairs. 1753. Rogers Fund, 1920, 20.40.1(22). © www.metmuseum.org

.jpeg)

This is a distinctly fashionable re-creation of medieval Gothic forms filtered through the eighteenth-century designers’ consciousness, and also a basic, token understanding of medieval architecture’s forms and characteristics. Indeed, there is no interest in recreating medieval furniture here, or medieval Gothic design in general. This is typical of fashionable Gothic furniture design from the early and mid-eighteenth century, and something that I have written about extensively—see my academia.edu page for details if you are interested.

Below - Fig.14: Detail of the c.1770 Gothic chairs in the Audit Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Below - Fig.15: Detail of the Humphrey Chetham tripod ‘Welch’ chair in the Audit Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

Below - Fig.15: Detail of the Humphrey Chetham tripod ‘Welch’ chair in the Audit Room at Chetham’s Library. © Chetham’s Library.

.jpeg)

A more curious example of Gothic furniture in the Audit Room is the ‘antiquarian’ tripod chair traditionally claimed to have belonged to Humphrey Chetham (Fig.15). This type of chair found popularity, like the Glastonbury Chair at St Chad’s, Rochdale, see here, in eighteenth-century Gothic interiors, such as Horace Walpole’s Gothic house, Strawberry Hill in Twickenham, London (Fig.16). You can find more detail on this chair type in an essay I wrote for The Furniture History Society Newsletter here.

Below - Fig.16: George ‘Perfect’ Harding, View of the Cloister at Strawberry Hill depicting the ‘Welch’ tripod chairs acquired by Horace Walpole. c.1839. SH Views H263 no. 1 Box 105. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Chetham’s heritage is tangible, incredibly precious, and currently at risk due to COVID-19 restrictions. Once it re-opens to visitors, it is well worth a visit from anyone, including locals, to appreciate this hidden gem! Your visit on a tour when they begin again will do much to help support the Library.

Image credits in the captions.

By Dr Peter N. Lindfield.