The seventh instalment as part of an ongoing series for Haunt Manchester by Dr Peter N. Lindfield FSA, exploring Greater Manchester’s Gothic architecture and hidden heritage. Peter’s previous Haunt Manchester articles include features on Ordsall Hall, Albert’s Schloss and Albert Hall, the Mancunian Gothic Sunday School of St Matthew’s, Arlington House in Salford – and more. From the city’s striking Gothic features to the more unusual aspects of buildings usually taken for granted and history hidden in plain sight, a variety of locations will be explored and visited over the course of 2020. In this article he explores ‘Manchester’s Modern Gothic in St Peter’s Square’.

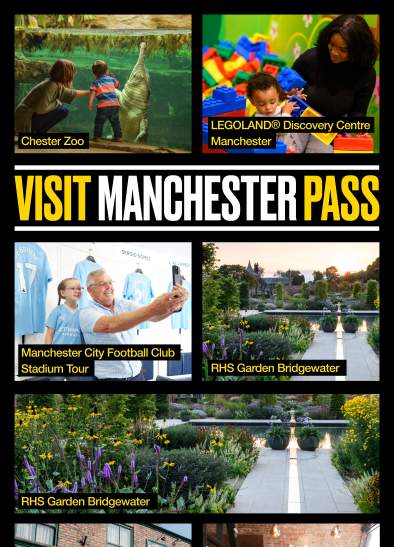

Above - Gothic additions to St Peter’s Square made during the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries. © Peter N. Lindfield.

Dr Peter N. Lindfield FSA is a Senior Research Associate in the Departments of English and History at Manchester Metropolitan University. He has published widely on Georgian Gothic architecture and design broadly conceived, as well as heraldry and the relevance of heraldic arts to post-medieval English intellectual, cultural, and aesthetic culture. Last year, as part of Gothic Manchester Festival 2019, he co-organised an event at Chetham’s Library Baronial Hall with Professor Dale Townshend titled ‘Faking Gothic Furniture’. This involved discussing the mysterious George Shaw (1810-76), a local Upper Mill lad who developed an early interest in medieval architecture and heraldry, going on to create forgeries of Tudor and Elizabethan furniture for a number of high-profile individuals and places at the time, including Chetham’s!

Currently Peter is completing his Leverhulme-funded research project exploring forged antiquarian materials in Georgian Britain, and also working on the recently re-discovered Henry VII and Elizabeth of York marriage bed, which itself was the inspiration behind many of Shaw’s so-called ‘Gothic forgeries’.

Below - Fig.1: J.M.W. Turner, Proposed design for Fonthill Abbey by James Wyatt. 1798. B1975.4.1880. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Below - Fig.2: Detail of the Central Bay of James Wyatt’s Heaton Hall, Manchester. © Peter N. Lindfield.

St Peter’s Square, an open space at the centre of Manchester, is the sight of the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 (see here) and today it is dominated by the tram interchange stations. Until the early twentieth century, however, the square was commanded by a church, St Peter’s, designed by the then most fashionable London-based architect of the day: James Wyatt (1746–1813). Wyatt was responsible for constructing some of the most significant country houses of late-Georgian Britain, including William Beckford’s stupendous Fonthill Abbey, Wiltshire (Fig.1), and, far closer to Manchester, Heaton Hall (Fig.2; see here for an essay on the building by Emily Oldfield and me).

His architectural style was mixed: Wyatt worked in both the Gothic and what has been termed the Neoclassical modes (a particular reinterpretation of Classical architecture that became prevalent in eighteenth-century Britain following, and informed by, discoveries made at the archaeological discoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum mid-century).

Above - Fig.3: Photograph of James Wyatt’s St Peter’s Church, Manchester. (CC-BY-4.0).

Above - Fig.3: Photograph of James Wyatt’s St Peter’s Church, Manchester. (CC-BY-4.0).

Wyatt’s church, as illustrated in Fig.3, was clearly in the Neoclassical style: it was a building erected from 1788 in a fashionable mode by a prolific and highly desirable architect. Pulled down in 1907—long before buildings were protected by the listing mechanism of English Heritage (now Historic England)—it is memorialized by a cross made from Portland stone, dating to 1908 (Fig.4). The irony is that this cross—an architectural memorial to an unlisted and destroyed building—is Grade II listed by Historic England (list entry number SJ8392997915); a status granted on 3 September 1974.

Below - Fig.4: The St Peter’s Church Memorial Cross, Manchester. © Peter N. Lindfield.

Below - Fig.5: The Eleanor Cross at Geddington. Lofty (CC-BY-2.5).

Below - Fig.5: The Eleanor Cross at Geddington. Lofty (CC-BY-2.5).

The St Peter’s Cross follows an architectural trope exemplified particularly by the 12 Eleanor Crosses erected to mark the place that the body of Eleanor of Castile (1241–90), wife of Edward I, rested overnight on its journey in 1290 from Harby, the place of her death in Nottinghamshire, back to London. Notable survivals of these crosses include that at Geddington, Northamptonshire (Historic England list entry number 1013313 (Grade I) Fig.5), and the cross at Charring Cross, London—in the forecourt of Charing Cross Station—is a Victorian recreation a short distance from the original’s location before being pulled down in 1643 (Historic England list entry number 1236708 (Grade II*) Fig.6).

Below - Fig.6: The Eleanor Cross at Charring Cross, London. Stephen Richards (CC-BY-SA-2.0).

Manchester’s St Peter’s cross is of a hexagonal plan (Fig.4) with five diminishing steps leading to the base of the cross (the sixth being a modern addition featuring uplighters). This base register includes an inscription carved in Uncial-type lettering—Roman lettering dating to the fourth century BC (Fig.7)—that reads:

'This cross erected ad 1908 records the place where the church of Saint Peter Stood from AD 1794 to 1907'

Below - Fig.7: Detail of the inscription on the St Peter’s Church Memorial Cross, Manchester. © Peter N. Lindfield..jpeg)

Rather than being built in the same style as Wyatt’s Church, the cross is Gothic: this is both curious and noteworthy. The choice to carve the memorial’s dedication in Uncial lettering, rather than a writing style typical of the medieval period matching the style of the cross’s architectural and sculptural form, is similarly curious and internally contradictory.

The memorial’s purpose is especially clear, and the decision to erect in in Gothic form does make sense—Gothic was the style of architecture most commonly associated with Christian churches, and this, therefore, refers suitably to Wyatt’s Church. The cross’s overt Christian imagery is clear: its cresting takes the form of a Christian processional cross and its central shield features, in typical Gothic Black Letter writing (unlike the Uncial inscription below), IHC, the first three letters of Jesus’ name in Greek (Fig.8).

Below - Fig.8: Detail of the ornamental cresting (with IHC) on the St Peter’s Church Memorial Cross, Manchester. © Peter N. Lindfield.

Between the base of the St Peter’s Cross and the cresting finial is a swept-in register including a quatrefoil—four-lobed cusp shape—panel with crenulated brattishing above. Out of this rises a clustered Gothic column—a device typical of revived Gothic architecture of the eighteenth century. Between the columns, standing on a pedestal, is an angel holding a shield that displays a pair of keys crossed; the heraldic shield ascribed to St Peter based upon his attribute of the key (to heaven) depicted in art (Fig.9).

Below - Fig.9: Detail of the ornamental detailing on the upper registers of the St Peter’s Church Memorial Cross, Manchester. © Peter N. Lindfield.

This is derived from the Gospel of Matthew, 16:19, wherein Jesus says to Peter, “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on Earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on Earth shall be loosed in heaven”.

The second structure considered in this post has nothing to do with religion, but twenty-first century commerce: Two, St Peter’s Square (Fig.10). This modern office structure was erected to designs by Ian Simpson Architects on the site previously occupied by four buildings: Bennett House; Century House; Clarendon House; and Sussex House. These buildings weren’t listed at the time of demolition; it was a controversial project given the significance of the Century House, which was built for the Friends Provident Society in 1934.

Below - Fig.10: North-West and South-West façades of Two, St Peter’s Square, Manchester. © Peter N. Lindfield.

Eddy Rhead from the Manchester Modernist Society also commented on the plans at the time - as seen here in a Manchester Evening News report. Further criticism of the proposed plan is recorded in the Architects’ Journal, and accessible here.

Below - Fig.11: Detail of the Gothic ornament on the South-West façade of Two, St Peter’s Square, Manchester. © Peter N. Lindfield.

The building’s north-west façade facing St Peter’s Square is simply a network of verticals and horizontals. It’s slim South-West façade, by happenstance—or perhaps not—facing the St Peter’s Church memorial Cross discussed above, presents a trio of different tracery patterns (based upon the tri-lobed trefoil; four-lobed quatrefoil; and intersecting circles) (Fig.11). All of these patterns are typical of, and clearly derived from, medieval architecture. The 11-story office building was constructed as a speculative venture (completed in 2017), but it blends the modern with the historic; the historic Gothic tracery patterns are also repeated in the building’s lobby as an illuminated installation (Fig.12).

Below - Fig.12: Interior Gothic screen in the Lobby of Two, St Peter’s Square, Manchester. © Peter N. Lindfield.

Both of the examples considered here demonstrate the vitality and continued relevance of the Gothic architectural aesthetic, even within the context of modern-twenty-first century additions to Manchester. Interestingly, this historicism effectively celebrates and perpetuates the city’s surviving Gothic architectural heritage that, rather than dating to the medieval period (such as the Cathedral), was forged in the Victorian period (Fig.13).

Below - Fig.13: Gothic additions to St Peter’s Square made during the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries. © Peter N. Lindfield.

.jpeg)

By Dr Peter N. Lindfield

Image credits - in the captions