The sixteenth instalment as part of an ongoing series for Haunt Manchester by Dr Peter N. Lindfield FSA, exploring Greater Manchester’s Gothic architecture and hidden heritage. Peter’s previous Haunt Manchester articles include features on Ordsall Hall, Albert’s Schloss and Albert Hall, the Mancunian Gothic Sunday School of St Matthew’s, Arlington House in Salford, Manchester’s Modern Gothic in St Peter’s Square, what was St John’s Church, Manchester Cathedral, The Great Hall at The University of Manchester, St Chad’s in Rochdale and more. From the city’s striking Gothic features to the more unusual aspects of buildings usually taken for granted and history hidden in plain sight, a variety of locations will be explored and visited over the course of 2020. In this article he reflects on a range of historic and architecturally significant Gothic towers in the Greater Manchester area. Whilst all the buildings mentioned are currently not open to the public at the time of writing (May 2020) due to the Covid-19 Pandemic, their striking towers certainly can be appreciated at a distance! This article is an opportunity to learn more about some of the history behind them.

Below - Perpendicular Gothic Tower of Manchester Cathedral. © Peter N. Lindfield.

.jpeg)

Dr Peter N. Lindfield FSA is a Senior Research Associate in the Departments of English and History at Manchester Metropolitan University. He has published widely on Georgian Gothic architecture and design broadly conceived, as well as heraldry and the relevance of heraldic arts to post-medieval English intellectual, cultural, and aesthetic culture. Last year, as part of Gothic Manchester Festival 2019, he co-organised an event at Chetham’s Library Baronial Hall with Professor Dale Townshend titled ‘Faking Gothic Furniture’ (it also features, along with The John Rylands Library, in a previous article by Peter, here). This involved discussing the mysterious George Shaw (1810-76), a local Upper Mill lad who developed an early interest in medieval architecture and heraldry, going on to create forgeries of Tudor and Elizabethan furniture for a number of high-profile individuals and places at the time, including Chetham’s!

Currently Peter is completing his Leverhulme-funded research project exploring forged antiquarian materials in Georgian Britain, and also working on the recently re-discovered Henry VII and Elizabeth of York marriage bed, which itself was the inspiration behind many of Shaw’s so-called ‘Gothic forgeries’.

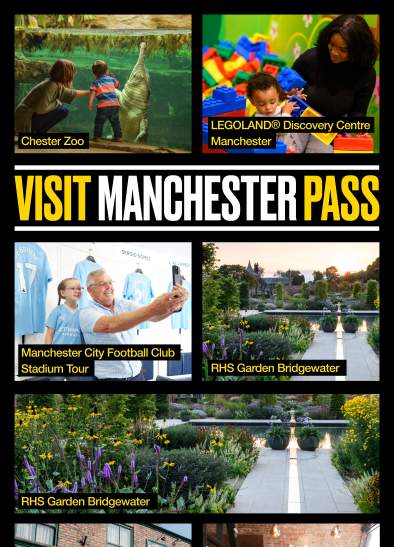

Cottonopolis: Reaching to the Sky - the history behind some of Manchester's Gothic towers

Above - Fig.1: ‘Manchester, Getting up the Steam’, The Builder (1853)

Above - Fig.1: ‘Manchester, Getting up the Steam’, The Builder (1853)

At the height of Manchester’s industrialisation, the city was awash with mills and their associated chimney stacks. This heritage lives on in the city, with mills converted into fashionable apartment blocks and their chimneys retained as pieces of industrial heritage. If we look at the representation of Manchester in an engraving, ‘Getting up the Steam’ from The Builder in 1853, chimney stacks belching out smoke abound (Fig.1). Turning to consider L.S. Lowry’s The Pond from 1950 and now in the collection of the Tate, it is possible to see the dominance of such chimney stacks (Fig.2). This imaginary depiction of industrialised Manchester—what is known as a capriccio—includes something else that today is easy to overlook, particularly given the seemingly endless construction of new high-rise blocks of flats: towers belonging to churches and civic buildings. I think it is possible to count five separate and clearly distinctive church towers in this painting: can you find these, and others?

Below - Fig.2: L.S. Lowry, The Pond. 1950. N06032. © The estate of L.S. Lowry/DACS 2020.

.jpg_tmp.jpg)

Lowry clearly realised the integral place of church and civic towers within Manchester’s industrialised landscape. Even so, these towers appear outnumbered by industrial examples: these were no ‘dreaming spires’ as we commonly think of in terms of Oxford (Fig.3). Even if Manchester doesn’t possess such associations, its medieval and great Victorian architecture is nevertheless all around. This post explores some of the most important, and perhaps forgotten, Gothic towers in the city.

Below - Fig.3: ‘Dreaming Spires’ of Oxford. Taken from Christ Church Meadows. © Peter N. Lindfield.

Below - Fig.4: Perpendicular Gothic Tower of Manchester Cathedral. © Peter N. Lindfield.

The earliest surviving tower in Manchester city centre belongs to the Cathedral (the fourteenth-century tower was extended in the Victorian period) (Fig.4) and is in the Perpendicular Gothic style and of the type exemplified by that at Gloucester Cathedral (Fig.5) notable for its corner pinnacles, and the battlements pierced with tracery patterns that form a parapet.

Below - Fig.5: Perpendicular Gothic Tower of Gloucester Cathedral. © Peter N. Lindfield.

Below - Fig.6: Manchester Town Hall. Mark Andrew (CC BY 2.0).

.jpg_tmp.jpg) At 87m tall, the central clock tower of Manchester Town Hall (Fig.6) is the tallest Gothic tower in Manchester and it proclaims the resurgence of the city. Designed by Alfred Waterhouse, a Manchester architect responsible for many Gothic buildings in the region—and London, the Town Hall’s spire from 1877 is matched by the spire on the earlier 1867 George Memorial (Fig.7) in front of the Town Hall by Thomas Worthington, another Manchester architect. The Town Hall’s tower is modelled largely upon the crossing towers of great cathedrals, such as Salisbury Cathedral in Wiltshire.

At 87m tall, the central clock tower of Manchester Town Hall (Fig.6) is the tallest Gothic tower in Manchester and it proclaims the resurgence of the city. Designed by Alfred Waterhouse, a Manchester architect responsible for many Gothic buildings in the region—and London, the Town Hall’s spire from 1877 is matched by the spire on the earlier 1867 George Memorial (Fig.7) in front of the Town Hall by Thomas Worthington, another Manchester architect. The Town Hall’s tower is modelled largely upon the crossing towers of great cathedrals, such as Salisbury Cathedral in Wiltshire.

Below - Fig.7: Albert Memorial, Manchester. Tim Green (CC BY 2.0).

.jpg)

Worthington was also responsible for the polychrome (bi-chromatic) tower on what is now the Minshull Street Crown Court complex (Fig.8), discussed in an earlier post, here. Modelled upon castellated architecture, this tower proclaims the rule of law and its defence.

Below - Fig.8: Minshull Street Crown Court. © Peter N. Lindfield.

.jpeg_tmp.jpeg)

Representing late Victorian Gothic tower architecture is the gatehouse tower with its very high pitched roof next to Alfred Waterhouse’s buildings for Owens College (Fig.9), next to Whitworth Hall, now part of The University of Manchester, discussed in an earlier post, here. It was built by Waterhouse’s son, Paul, c.1895–1902, and this tower recreated collegiate gatehouses seen in many examples of medieval and early-modern architecture in places such as Oxford, Cambridge, and further afield.

Below - Fig.9: Whitworth Hall, University of Manchester. Stephen Richards (CC BY-SA 2.0).

A number of churches were built in Victorian Manchester with incredibly tall, vertiginous spires drawing one’s eye upwards to heaven. They include that on St Mary’s, Hulme, designed by J. S. Crowther, and built in 1853–58 (Fig.10). The crossing tower of Salford Cathedral (Fig.11) is also highly vertical, yet lacking the coherence and sheer height of St Mary’s spire.

Below - Fig.10: Church Of St Mary in Hulme. Julie Anne Workman (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Below - Fig.11: Salford Cathedral. Ian Roberts derivative work of Rabanus (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Further, far more modest towers are found at the end ‘The Gorton Monastery’, a former Franciscan friary, designed by E.W. Pugin in the 1860s (Fig.12), and also at the centre of what is now the British Muslim Heritage Centre in Whalley Range built from 1840 as a congregational college (Fig.13).

Fig.12: The Monastery, Gorton. Sue Langford (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Below - Fig.13: British Muslim Heritage Centre, Whalley Range. KJP1 (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Manchester architecture may well have reached for the skies with brick-built chimney stacks as part of its industrialisation, but civic pride and religious fervour also saw architects build tall, Gothic towers. Such examples can also be found throughout Greater Manchester, including, perhaps most notably at Rochdale Town Hall (see our full Haunt article here), where the original Victorian tower was replaced by the 1885–87 example seen today (Fig.14) by Alfred Waterhouse following the earlier example’s heavy damage by fire. These are quite overshadowed by new skyscrapers, but the religious and civic towers in the city and Greater Manchester nevertheless record and demonstrate heritage.

Manchester architecture may well have reached for the skies with brick-built chimney stacks as part of its industrialisation, but civic pride and religious fervour also saw architects build tall, Gothic towers. Such examples can also be found throughout Greater Manchester, including, perhaps most notably at Rochdale Town Hall (see our full Haunt article here), where the original Victorian tower was replaced by the 1885–87 example seen today (Fig.14) by Alfred Waterhouse following the earlier example’s heavy damage by fire. These are quite overshadowed by new skyscrapers, but the religious and civic towers in the city and Greater Manchester nevertheless record and demonstrate heritage.

Below - Fig.14: Rochdale Town Hall. AdamKR (CC BY-SA 2.0).

By Dr Peter N. Lindfield

Photo credits in the image captions